Blockheads #2: 1950-51

First published May 1, 2020

I. (feelings)

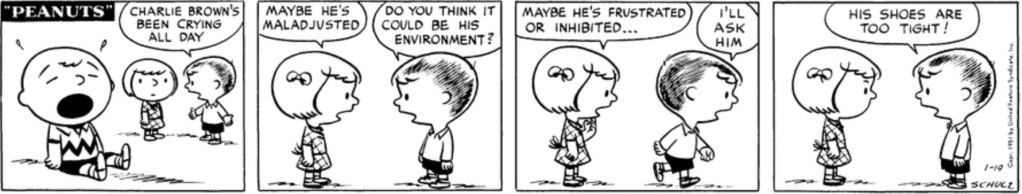

Before “good grief,” there was “great Scott!”

A big part of the pleasure involved in going back to the beginning of any beloved artwork is discovering which elements were present from the first and which evolved along the way. A big part of the discomfort: discovering that the most important elements, as you see them, were relatively late arrivals. The Van Pelt kids, my favorite Peanuts characters, don’t show up at all in the first year of the strip: we’ll meet them in 1952. Snoopy is adorable—cuter, actually, than he would become from the late ’50s on—but, with his sweet disposition and puppy-dog eyes, just about unrecognizable. And that expression of frustration that sounds like a blessing, which would come to stand in so perfectly for the strip’s bittersweet mood, still hasn’t shown up as of December 31, 1951. In its place, a phrase that might have referred to Sir Walter or General Winfield or perhaps simply arose as a corruption of the Austrian “grüss Gott” (thanks, Wikipedia) just doesn’t have the same paradoxical charm.

I had seen enough early Peanuts installments, and read enough about the strip’s origins, that I was prepared to feel no real connection to the artwork or the jokes in this first volume of the Fantagraphics series. I dreaded—I don’t know what; something like the uncanny sensation of absence you get when looking at a picture of your parents in early adulthood; and I responded to dread in my usual way, by ratcheting down my expectations and cultivating detachment. I wasn’t entirely wrong about this: compared to the many-layered emotions that a typical strip from the ’60s activates in me, the sight of these early “li’l folks,” whose heads are wider than they are tall, produces a Capgrasian numbness. But, probably thanks to my overcompensation, I found myself more often surprised by the familiarity of these early strips—not because they match the heights of peak Peanuts, but because (it seems to me) I can make out the intermediate steps that would get Schulz there.

II. (readings)

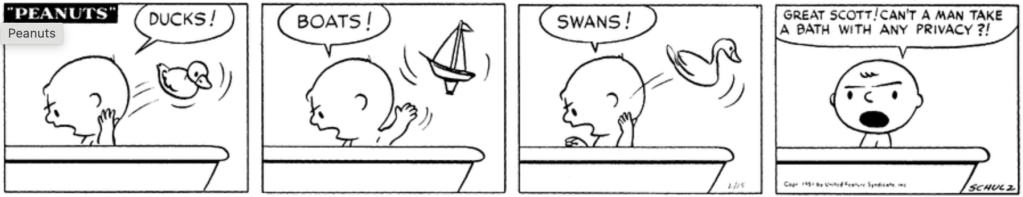

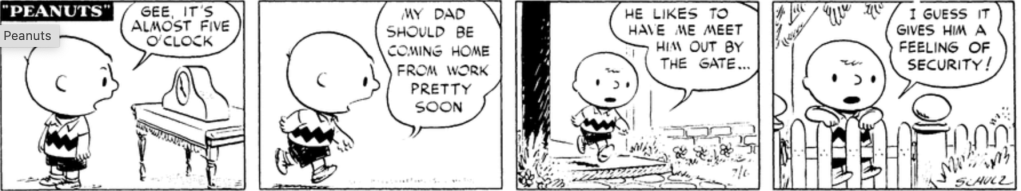

Take, for instance, this very early strip, from January 1951—only a couple of months after Shermy famously introduced us to Charlie Brown with a blankly malicious “How I hate him!”:

It’s a common enough gag structure from early-’50s Peanuts: kids who combine grown-up knowledge with childish tastes, habits, and limitations. And it is funny, I think, to see a couple of expressionless infants speculating that one of their peers may be “maladjusted”! Chuckle funny rather than deep-inward-smile funny, but still.

People who never got profoundly invested in Peanuts, but know that it has a reputation as a “smart” comic strip, often seem to believe that this kind of joke characterizes the whole 50-year oeuvre—that Schulz got 18,000 micronarratives out of “what if kids talked like adults?”. It’s an understandable assumption, and if it were true, there wouldn’t be much value to an encyclopedic investigation of the strip, except of course for “fanatics” (a favorite word of Schulz’s). But when I read the strip above, it immediately brought to mind this one from a decade later:

First, let’s synchronize our taste: the second strip is definitely better, right? The drawings are much funnier and more expressive, not only, but partly, because the characters’ bodies are built for comedic expression (Linus’s reactive hair, the kick of Lucy’s stiff little skirt). The roles are more appropriately distributed and differentiated across characters: we have the neurotic kid, the older sister helping him tie his shoes, and the confused bystander who stands in for the reader. The pacing and structure are better: through the kids’ odd posture in the first three panels, Schulz gives us enough partial information to pull our gaze and our attention through the strip, indicating that something funny is going on but that we’ll have to keep reading to learn what it is.

The ’61 strip is funnier in all these little ways. It’s also, I think, more sophisticated and more characteristically Schulzian in a way that’s slightly harder to unpack. The structure of the ’51 strip is deflationary: these little kids are using big words and complex social-scientific concepts to talk about their friend, but really his shoes are just too tight. In the ’61 strip, it would at first appear, the gag is even simpler: Linus is just excessively picky about his shoelaces. But both the intensity and the articulacy of his reaction (“I feel flimsy”) suggest that, unlike the infant Charlie Brown’s despair, Linus’s distress is both about shoelaces and about something more profound, something that might be (clumsily) paraphrased as the balance between freedom and a firm grounding. The relationship between these two factors, one physiological and one psychological, isn’t exactly one of displacement or substitution or even symbolism. My paraphrase above is clumsy in part because it really isn’t right to suggest that two fundamental human values are doing battle within Linus here; it’s more that he’s trying to steer between two affects, both unpleasant, between which might lie some temporary peace. But that struggle to keep out of discomfort, in which most of us spend a high percentage of our days engaged without even necessarily feeling ourselves doing so, is itself a meaningful part of being human—one that need not mean anything in its own right to shape and structure our moods, beliefs, morals; and one we have to restart continually, often without any discernible progress, whatever progress might even mean. (This is why, for the record, it’s shoelaces and not shoes in the second strip; not just because they can be adjusted, but because they have to be adjusted every day.)

An overreading? Maybe! Linus’s emotional rollercoaster ride is about mere shoelace tightness, I not only concede but insist. What I’m getting at is: that doesn’t mean it is merelyabout shoelace tightness. And the relationship between a person’s psychological foundation and their picky habits isn’t one of dependence; it’s more like a mixture. That, I think, is part of Schulz’s background theory of the mind, at least as it was developed over time. And you can see how starting from a bunch of little creatures with vocabularies that outpace their bodies would get you there, eventually, if you were sensitive and sympathetic and bent on making those creatures human.

III. (theories)

This leads me to something that, with a little chagrin, I think I have to call a methodological point. Through Schulz’s telescope, the distance between the silly things and the serious things gets collapsed: everyone who has read and loved his strip knows this. But the very fact that I was able to place the 1951 and 1961 strips next to each other attests to another trick of scale by which Schulz stretched the affordances of the comic strip medium itself.

Like D.A. Miller pausing and rewinding a Hitchcock film on DVD, I am very aware that my approach to Peanuts in this project departs from how the strip was ostensibly meant to be read. A newspaper strip is parceled out day by day on the comics page. If it’s as successful as Peanuts, it does get reprinted in books, thousands of them, but most don’t have the scholarly apparatus or the chronological continuity that you would need to get systematic in your reading; they look more like the “Peanuts Classics” volumes I hoarded when I was a kid, loosely collected by theme and era:

(Incidentally, even though I’m a grown adult who has committed to investing in the entire Fantagraphics set, the cover of Summers Fly, Winters Walk still gives me a clutch of possessiveness, because that book always seemed to be checked out of the Sequoya Branch Library when I wanted it.)

So being a Peanuts completist already means defying the rhythm of the daily comic strip, just as bingeing a pre-Netflix sitcom like Newsradio always feels like going against the grain. But at least the grand reading project of this newsletter preserves the historical sequence of the strips. The comparison I drew in section II was even more perverse, because there’s just no way that a sane newspaper reader, or even a sane sequential reader of the Fantagraphics books, would remember a one-off joke from January 1951 by the time May 1961 rolled around. If I, a hopefully sane Peanuts lover, did spontaneously make the connection, it’s because I’ve read and reread certain eras of the strip so many times that individual strips exist in my brain the way lines of poetry or baseball stat lines do for other obsessives.

I’m going to keep making those connections, in part because I can’t help it (“I feel flimsy”: I have definitely thought that line to myself before), and in part because I genuinely believe that this, and not some more naïve or more historically responsible approach, is the right way to read Peanuts. Here is my hunch: whether or not it was Schulz’s animating intention at any given moment, his greatness forced him to work through concepts and themes over and over, both to get them right and to capture their complexity. (In the scale-free world of Peanuts, where tiny components make patterns over distances too great for any daily reader’s perception, “too-tight shoes” can qualify as a theme.) If he were Proust, he might have gone back to the “His shoes are too tight” scene and appended a long paragraph offering an alternative interpretation. (“And yet to say that his shoes were too tight is not necessarily to say that he did not suffer as greatly as others do from more legitimate causes …”) But he was Schulz, and so he simply did it again. Not necessarily on purpose, but in a way that we can legitimately treat as intended, according to whatever more-than-human intention can sustain itself over the course of a life.

IV. (rituals)

To close, a couple of institutions I’d like to install in this newsletter. One acknowledges the first time something or someone appears in the strip; the other offers a decontextualized panel that made me laugh or brought me happiness. Together, they’ll close each of my installments, along with a signature you may recognize from Charlie Brown’s letters to his “pencil pal.”

First of the Week:

There are so many “firsts” this week, of course: first appearance of Charlie Brown, Shermy, Snoopy, Patty, Schroeder, Violet; first time Snoopy imitates another animal; first mention of Beethoven, and first time he’s associated with Schroeder; etc. To keep you on your toes, I’ve chosen the first manifestation of one of Peanuts‘s most characteristic themes: security. Before it was provided by a blanket, before it was defined as “sleeping in the back seat of the car,” security was something Charlie Brown tried to give his dad.

Panel of the Week: