Blockheads #3: 1952

First published May 9, 2020

I. (a proposition)

Peanuts became Peanuts between May and December 1952.

I didn’t expect to make a discovery like this! I figured the strip would gradually come into its own, adding tropes and characters at a rate of a couple a year until one day, sometime perhaps in the late ’50s or early ’60s, I would look around and realize that I was now beyond a doubt reading Peanuts. And, to be clear, many aspects of Peanuts as of New Year’s Eve 1952 are quite different from what the strip would be at its height. For one thing, some of the main characters are still, literally, growing: Lucy goes from a huge-eyed babbler to an articulate fussbudget over the course of this year, while Linus hasn’t learned to talk at the end of this volume. The art is still a bit busy, a bit squat and cutesy, compared with Schulz’s late ’50s work; the kids are still learning the gestures (outstretched declamatory arms, a hands-in-pockets slouch) that will eventually become automatic; Snoopy still looks like an actual pup with a normal-sized nose; etc. But I think you’ll begin to understand my shock when you see what happened to three of our central characters, not just in this year, but specifically from May of this year on—seven months of real life, an afternoon of reading time.

II. (changes)

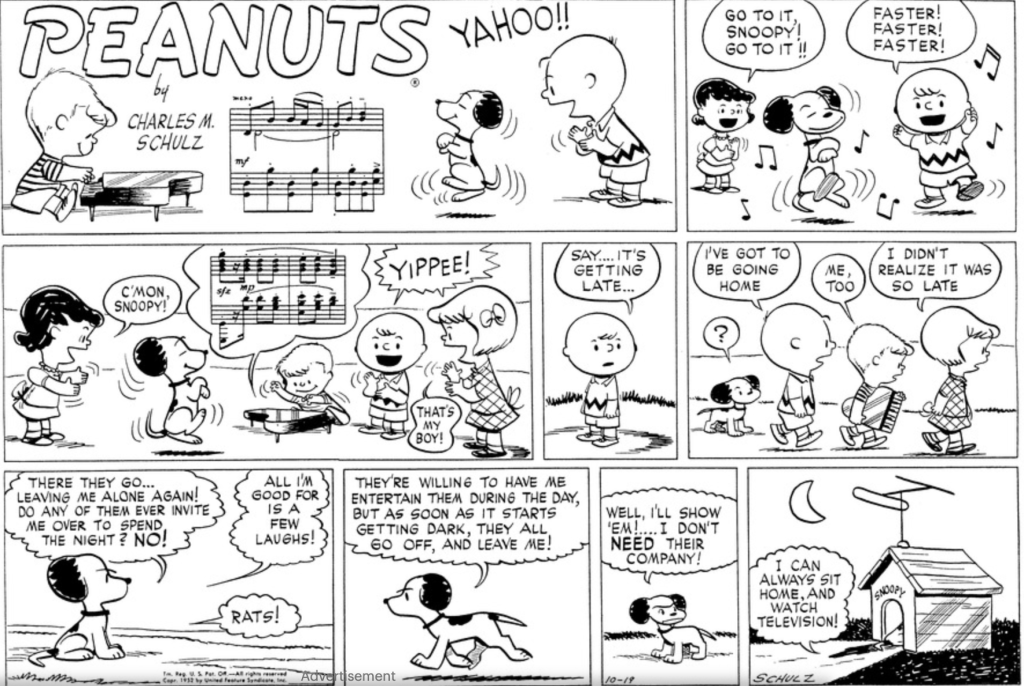

On May 27, 1952, Snoopy has his first thought balloon, which, by October, has developed into a full stream of consciousness:

This strip—a Sunday strip, you’ll note, and it’s no accident: 1952 also marks the first year that Peanuts began appearing every day of the week—strikes me as a breakthrough for the character on a number of levels. Yes, it’s his first multi-panel interior monologue, and one that expresses a key preoccupation of early Snoopy’s: his resentment at being left out of human pursuits. But it’s also the first time we learn that he does have unexpected access to some human pursuits, through the magical space of his doghouse that is more than a doghouse. In other words, it’s the first indication that Snoopy has an imaginative life outside of the kids in the neighborhood, meager as it seems compared to his later flights. And it’s the first time we see Snoopy in bipedal mode, a feat he achieves—appropriately, in retrospect—through le danse.

It will be several years, of course, before Snoopy regularly walks on two legs. And Schulz would take some time to develop conventions around these new features: thought balloons rather than the odd cloudlike speech bubbles we see here; a side view of the doghouse that makes its depths more mysterious. (This 1952 doghouse is a plausible three-dimensional object, which will not be the case for long.) There was plenty of backsliding along the road to a more humanlike, or at least a more personlike, Snoopy: a week or so after the strip above, he’s even playing fetch, a pastime that mature Snoopy consistently scoffs at. (Yes, that’s an infant Linus in the last panel, already wiry-haired.) I suspect it’s precisely because Snoopy isn’t yet a member of a social circle, doesn’t interact verbally with the human kids, that he develops more slowly and erratically than the other characters; my reasoning will, I think, become clear in section III below. Even so, Schulz has by the end of the year cleared some runway for Snoopy’s future trajectory.

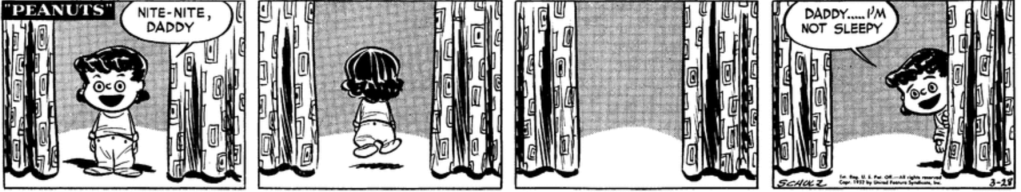

Lucy begins to look like herself once she develops the characteristic half-circles around her eyes (a Van Pelt family trait, since Linus and Rerun have them too): they first appear in profile, but become standard from all angles by June ’52. Before then, for the first few months of her existence, her eyes are startlingly saucery and, to be honest, pretty cute (dig that postwar decor, too):

In these earliest strips, she also often refers to herself in the third person (“Poor Lucy!” is a bit of a catchphrase—imagine anyone, least of all Lucy, saying that by 1960!) and speaks in baby babble that Schulz, fortunately, seems to have abandoned pretty quickly. Baby Lucy is mischievous—she enjoys inconveniencing Charlie Brown and that unseen “daddy”—but certainly not cruel, and entirely lacking the capacity for complexly ugly feelings like resentment, officious pride, or “sheer jealousy“.

But as early as August 1952, only six months after her introduction, Lucy is trouncing Charlie Brown at checkers, talking like any other Peanuts character, and displaying the kind of manic egotism and hair trigger for violence that would eventually be her trademarks. Apart from some details of the art and the telltale “Great Scott!”, this could easily have been a strip from the late ’50s:

The joke is not generic but Schulzian (the gleefully overblown “a grand coup!”); it’s enacted with the right characters, gloating Lucy and defeated Charlie Brown (although later Charlie would probably have accepted his defeat more willingly); and the timing is, if not perfect (note the stacked word balloons in the second panel), pretty close to it.

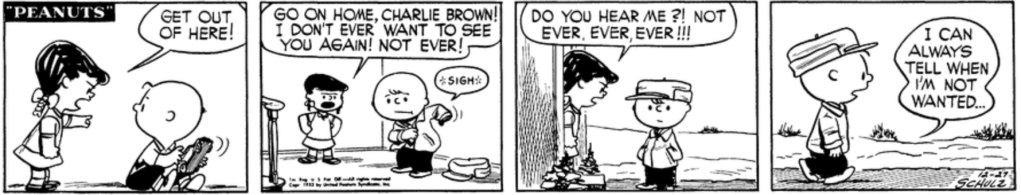

The strip above gives you some hint of the last major development, perhaps the most important of all. By December 1952, Charlie Brown has become, without any doubt, a loser. Here’s the last strip of the year:

This could have been a one-off, of course, but here’s the strip from two days before:

And from two days before that:

You get the idea. Charlie Brown was the target of plenty of jokes in the first year of Peanuts, of course, but the score sheet remained more or less balanced: Patty would comment on his huge head and he would chase her out of the last panel; a day or two later, he would insult Patty and she’d chase him out of the last panel; and the strip rolled along in an atmosphere of mild, evenly distributed meanness. It may sound like cold comfort, but even the infamous “How I hate him!” punchline is delivered only once Charlie Brown is out of frame and, presumably, of earshot. In the three strips above, though, Violet’s behavior can’t even really be described as meanness, because that’s designed to get a reaction out of the victim: she’s simply expressing her unfiltered and non-negotiable feelings about Charlie Brown, which range from indifference to irritation to a loathing for the very sight of him. Taken together, this accidental (?) series establishes a pattern of blunt antipathy to which Charlie Brown responds with a depressive passivity that will only deepen with time. Just think how many more times he’ll heave that “*sigh*” we hear as he’s putting on his coat!

So: Charlie Brown as social pariah seems to be an invention of fall/winter 1952; every empty-handed Valentine’s Day, every coldly ringing “Ha! Ha! Ha!” when he does something dumb, every lonely lunch hour stems from here. But if this December sees a Charlie Brown on his way to full ostracism, it’s partly because the preceding months have established him as someone who loses at everything—improbable, fantastical, unending losses. In two strips from the same week in May that saw Snoopy’s first words, Charlie Brown’s baseball team suffers its first monumental defeats, which by day two (“Did you lose again today, Charlie Brown?”) we’re already encouraged to read as part of a pattern. (Disorientingly for old Peanuts hands, Charlie Brown is the catcher in these early games, not the pitcher.) August ’52 even sees the first appearance of a phrase so emblematic that it titled a Peanuts paperback from my youth, one I assumed would only appear much later: “There goes [the] shutout!”

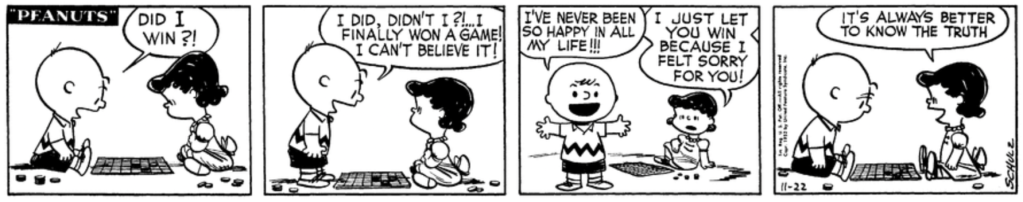

Charlie Brown’s first failure to kick the football isn’t far behind. And that checkers loss to Lucy wasn’t the last of its kind: the very week of the football mishap, Lucy beats Charlie Brown (presumably at checkers, although the board gets more and more abstract and schematic) three days in a row, making for “three-thousand straight games” of defeat. On the fourth day, it seems the tables have turned:

In a few months, Charlie Brown has gone from expecting to win (and being enraged by losing) to expecting to lose (and pathetically rejoicing when he thinks he’s won). The mood reminds me, somehow, of a strip from a few weeks later in which Patty and Violet manage to turn Charlie Brown’s affability into a negative character trait, introducing the term “wishy-washy” in the process. Look at his body language in both: the worry and sorrow in the eyes, the slumped shoulders, the drooping balloon of the head. His shape would change a bit over the coming years, his expressions become a bit more focused and formalized, but “let’s face it, Charlie Brown”: that’s you.

III. (theories)

“It’s always better to know the truth.” The last panel in the strip I quote above is as perfect and typical an interaction between these two characters as any you’ll find in later years. Charlie Brown, primed for failure but all too ready to hope; able to take joy and pride in the smallest victories, but all the more easily crushed because of that. Lucy, casually tanking his self-esteem for what seems like no particular reason; articulating a deflationary philosophy that will motivate her most callous actions, from stripping Linus of his blanket again and again to making Charlie Brown sit through a slideshow presentation on his faults. The recurrence of the football ritual from year to year will eventually make it obvious, but already in the checkers sequence, these two are locked in. As imaginary people, they’re trapped in the most unhealthy of cycles; but as characters, as products of Schulz’s art, they need each other.

Why, then, did Peanuts become itself all at once over about seven months in 1952? Because Charlie Brown and Lucy got stuck in a positive feedback loop that made both of them into characters—no: through which they made each other into characters. Yin and yang, moon and sun, wishy-washy and fussbudget.

Many analyses of Peanuts—mostly, I can’t help but observe, written by men—seem to assume that Lucy’s character entirely coincides with her destruction of Charlie Brown’s dreams. I find this argument frustrating insofar as it deprives Lucy herself of any personality or consciousness; in its most extreme form, as Chuck Klosterman articulates it for instance, “Lucy represents the world itself,” responding to Charlie Brown “the way society always responds”. (Klosterman makes this point in his wonderfully titled essay “There’s Something Peculiar About Lying in a Dark Room. You Can’t See Anything.”) A reading like this, in my uncharitable paraphrase, makes Lucy a descendant of the mean mother figure conjured by 19th-century American novelists, always cramping the style of masculine dreamers by speaking for “society.” As I’ll surely be arguing over many letters to come, Lucy has her own anxieties and despairs and moments of profound loneliness; part of Schulz’s greatness was to imagine those. But reading 1952 helped me see a truth in those Klostermanian readings of Lucy that I hadn’t seen before: more than any other character, more even than Snoopy, Lucy is bound to Charlie Brown. The connection between the cruelty of the one and the failures of the other is not accidental; it is foundational.

Or rather, it’s both accidental and foundational. Like DNA, or the last Ice Age. Absolutely nothing in baby Lucy, scampering around in what she cutely called her “sleepies”, required that she become the gleeful dispenser of painful truths that we see in the checkers strip. And—this feels unthinkable, but it seems to be true—nothing in early Charlie Brown required that he become lonely and sad and hapless and lovable. It could have been Shermy who lost that first checkers game to, say, Violet; nothing prevented it, then! But because Charlie Brown and Lucy happened to make each other, Schulz could go on to make Linus and Sally and Peppermint Patty and even, on a lesser scale, Violet and Shermy. The characters we know were formed by a combination of chance and sociability, like everybody.

IV. (rituals)

First of the Week:

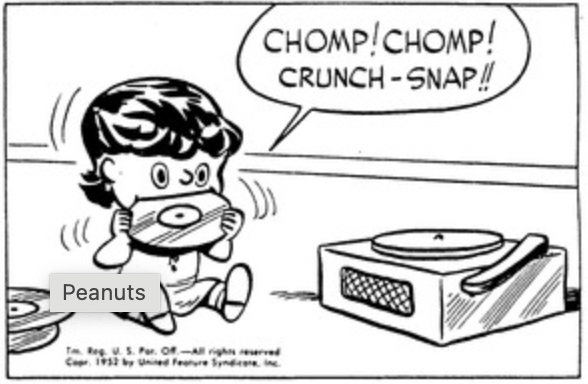

This week’s letter is all about firsts, of course, so I’ll have to reach for a deep cut: the first folded-over sandwich. Schulz’s characters, especially the Van Pelts, are quite consistent in their preference for sandwiches made out of one piece of bread folded in half rather than two sliced half-pieces. Don’t ask me why, just marvel at young Lucy’s certainty:

Panel of the Week:

Your friend,

Hannah