Blockheads #4: 1953

First published May 15, 2020

I. Mothers; or, notes on the psychopathology of fussing

Last week, I mentioned that men who write essays about Peanuts usually have little sympathy for Lucy, who stands in for the unfeeling, inflexible world that beats Charlie Brown down. But Lucy has her own bone to pick with the world of adult expectations—how else to explain her fussbudgetry, on which 1953 sheds increasing light?

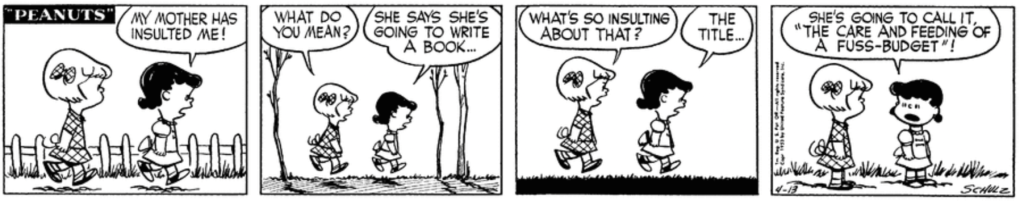

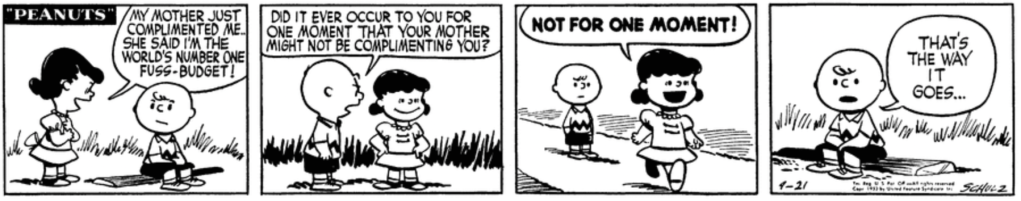

Based on these hints, Lucy’s relationship with her mother seems, as a Peanuts character would say, “fascinating!” The fussbudget (or, at this stage, “fuss-budget”) concept exclusively appears this year as a term that Lucy’s mother applies to her—sometimes even, apparently, when talking to other children about her own daughter. (I recognize that Schulz needs to set up the joke, but the scenario this implies—that Patty, say, is strolling down to the Van Pelt house to gossip with Lucy’s mom about Lucy—is pretty wild.)

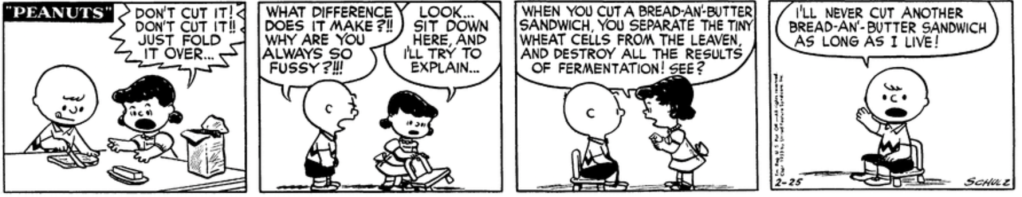

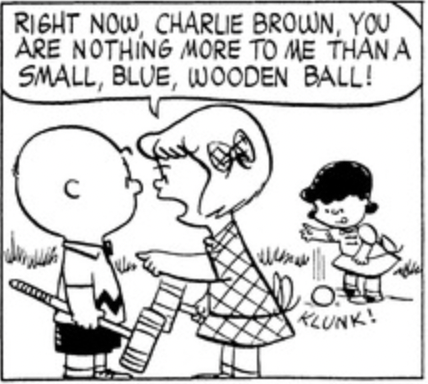

Lucy’s fussbudget tendencies, in other words, were first visible to (and, presumably, most aggravating to) her mother. And one can see why, because “fussing,” at least as practiced by Lucy, isn’t just about being irritable or loud; it’s specifically about rejecting as inadequate the care work of the people responsible for your well-being. Even when they’re only temporarily responsible—say, when making you the bread-and-butter sandwich you asked for:

In this era, Lucy is always asking Charlie Brown for sandwiches, and she’s always fussing about his unsatisfactory technique. Can you imagine, based on this one example, what Mrs. Van Pelt’s life must be like? In the 1950s suburbia of Peanuts, after all, the person who’s most responsible for your well-being is your mother. You can fuss in anybody’s presence and for whatever reason, but the person you are really fussing at is always your mother, and she knows it.

Now, we get only occasional glimpses of the care work that the Peanuts mothers do—never directly, and usually through objects like the brown-bag lunches that their kids unpack at school. (“Peanut butter again! Oh, well, Mom does her best.”) The invisible structuring force that mothers exert on the Peanuts world becomes visible only when it fails, as during the infamous week in 1962 when Mrs. Van Pelt’s new pool table seduced all the mothers of the neighborhood away from their domestic duties. I’m deviating from 1953 a bit here, but follow me for a moment:

This strip suggests two things, one by straightforward implication, one more indirectly. The first is that every time we see Violet with her ponytail in the world of the strip, it’s because her mother brushed and styled her hair that morning. (How perfectly Schulz represents those loose hanks of uncombed little-kid hair!) This makes realistic sense: I don’t remember when I learned to make my own ponytail, but I was almost certainly older than 6 or 7, which I’m guessing is about Violet’s age here. But whereas my mother put my hair in a ponytail relatively infrequently in those days, Violet wears her ponytail every day—and this brings us to the second, sneakier point. Violet’s ponytail is not just an incidental part of her character; it’s the feature that allows us to recognize her, the economical index of identity that Schulz has given her, akin to Marcie’s glasses or Patty’s bow. (In the early days, including into 1953, Violet sometimes wore pigtails, but she’s always had a -tail of one kind or another.) If we hadn’t known this going in, Linus’s question in the first panel above would make it clear: over the preceding decade, Schulz has done the work to make sure that we see ponytail and think “Violet,” hear “Violet” and picture ponytail. And we learn here that while Schulz is responsible for the ponytail in our world, Violet’s mother is responsible for it in the strip’s world.

The day-in, day-out labor of maintaining a (fictional) person, keeping them consistent, keeping them legible … Schulz doesn’t seem to have had particularly progressive ideas about gender and parenting, but is his work on the strip so different from a mother’s work? If a book is a novelist’s baby, that baby can grow up—that is, can circulate in the world relatively independent of its author, without the need for constant touch-ups. But the Peanuts kids never grow up, and the Peanuts strip never, except by the accidents of old age and incapacity, floated free of Schulz’s hand; that’s not how comic strips work. They don’t finish, or reach maturity—they just keep going till they don’t, and in the meantime there’s always another panel to ink.

Schulz is thinking about mothers in the early- to mid-1950s; of this I’m certain. (Apart from all the references above (and others that don’t explicitly mention fussing, but have much the same flavor), Lucy’s mother actually talks in this era. The indispensable index to the 1953-1954 Fantagraphics volume has a listing for “adults, audible”, knowing that any Peanuts fan would find this noteworthy: adults famously don’t speak in the TV specials, and eventually their voices disappear from the strip as well, leaving us with only the child’s side of the conversation. But right after that index entry, we find this note: “(Lucy’s mother unless noted)” (317). In other words, an adult voice that doesn’t belong to a mother, specifically Mrs. Van Pelt, is as notable as a Violet without a ponytail. I haven’t yet read Schulz and Peanuts (although I plan to!), so I have next to no information about Schulz’s own mother or his attitudes toward mothers (or fathers or grandfathers, who are mentioned more often as the strip goes on). But I think he knew about the endless, often monotonous, often exasperating work of keeping something alive.

Which makes Lucy’s fussing all the more interesting. Her fussing is sometimes about demanding more or better care (fold it over!), but I usually read it as a general comment on how irritating it can be to be cared for—to have a mother who makes you share with your baby brother and notices when you got into the cookies and keeps you home when you’re sick, a mother whose voice you can hear. As the kids in Peanuts gradually detach from their fictional parents, though, Lucy’s fussbudget status quietly fades and is replaced—mostly by active villainy; occasionally by grudging care for her little brother. When it’s a mother in charge, we don’t hear about the frustrations of caring, just those of being cared for. Once Lucy assumes responsibility for Linus, we begin to see both—the desire to pat birds on the head, and the panic about what society will think; blanket-dependency, and attempted interventions; the longing to see the Great Pumpkin, and the need to get your little zealot home and into bed before he gets frostbite. I’m not quite sure what to make of this, to be honest. Like a not-quite-right bread-and-butter sandwich, Linus is unsatisfactory to Lucy, which is a kind of caring, maybe, just not the kind that makes anyone feel better.

II. Interlude: a thank-you note

I hope everyone who takes even a casual interest in Peanuts knows about the Fantagraphics series by now, but if not: boy, do I love these books. They’re quite handsome and well-printed and (obviously) complete, with introductions by famous and interesting people, but there’s one thing, mentioned above, that makes them indispensable: the index. The Index!! As the kind of person who really wishes there were a way to include footnotes in these letters, you know I worship The Index. I bought the paperback edition of the first volume (1950-52) and it was less expensive and quite fine-looking in its own right, but it doesn’t have The Index, so I’m committed to the hardcovers from here on out. I guess that’s what you’re paying for, which seems entirely fair.

For those of you who have not seen The Index, it’s exactly what it sounds like: a comprehensive list of subjects covered in any given Peanuts volume, with page numbers for reference. A typical extract: “chocolate creams […] Chopin, Fryderyk […] cigar-box banjo […] clowns […] clouds […] coco(a)nut, distastefulness of” (317). Those are all fairly rare topics (although coconut puts in a good showing). By contrast, “Snoopy” has countless entries, some of which are sorted into subheadings: “ears […] insults to dog-ness of […] thinking […] (in word balloons)“.

That last example gives you some sense of what’s so magical about The Index: it is clearly designed for scholars. Or, at least, for the kind of person who cares whether Snoopy’s thoughts are represented in traditional thought balloons or word balloons or an odd hybrid of the two. Of course, if you just want to find that one joke about “Das Wohltempierte Klavier,” The Index can help you there too, because The Index was clearly compiled by someone who loves Peanuts and understands the odd fractal familiarity of its fans. If you know anything about the person or persons who compiled The Index, please point me their way so I can send them flowers and buy them a beer when we’re able to go to bars again. You, stranger(s), have brought me intense happiness and furthered the cause of knowledge.

III. Postlude: More about Violet

Did you know that Violet has a last name? It’s “Gray.” Violet Gray—a fine name and a color I can almost imagine. I meant for this letter to be about Violet and Patty, the two functionally interchangeable girls whose main role in this era is not inviting Charlie Brown to parties, and who stand out among the Peanuts characters for being mean but not themselves neurotic. It was going to be an appreciation of them—their beautifully bland conversations, their social savvy, their passion for critique. Then, in what was supposed to be a short introduction about Lucy-as-fussbudget that served to transition into their callousness, I noticed the mother motif and followed it here. Patty and Violet, this isn’t the first time you’ve been passed over, and I apologize. I pledge to give you your due one of these Fridays.

IV. Rituals

First of the Week

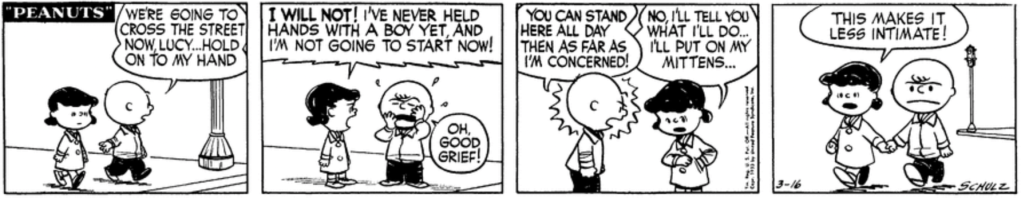

Ever since I made you aware of “great Scott!”, you’ve no doubt been waiting for “good grief!” to take its rightful position. I’ve got good news for you:

Panel of the Week

Your friend,

Hannah