Blockheads #6: 1955

First published June 12, 2020

I. A bouquet of Blockheads

Maybe my already-weakened attention span has gotten even more feeble lately, or maybe 1955 just offers too many interesting things to write about, but I think this week’s Blockheads is going to be a handful of short takes rather than a unified argument. That’s my first programming note of the day. Here’s the second:

This whole enterprise may feel frivolous to you at the moment. It does to me, because even though I firmly believe that Peanuts is art and grants us access to truths about humans just as all art does, it is also the case that any given artwork can wait. (It will always wait for you, faithfully—that’s one of the truths.) But I’ve heard from people who are doing hard work and experiencing grief and fear that Blockheads is a pleasant part of their routine, so I’m going to keep it going. It certainly keeps me going—

For some it’s Beethoven; for others it’s paper dolls; for others it’s Peanuts.

For some it’s Beethoven; for others it’s paper dolls; for others it’s Peanuts.

For a number of reasons, these newsletters will be biweekly until the end of June, but after that I’ll return to a weekly schedule. I hope you’re spending the interim reading about prison and police abolition, thinking about how to dismantle the racism built into all American institutions, and taking action in your daily life to make sure that Black people get listened to and get paid. Check out 8 for Abolition, write to your elected officials, attend your city council meetings, and keep this wave of action going. Thanks for listening! Here’s a big bag of Blockheads Minis.

II. Appeal to authority

In my dad’s extended family, we do something called “going to the dictionary.” It’s one of my deepest associations with family gatherings at my grandparents’ house, along with the smell of takeout pizza from Jake’s. Every so often, the grown-ups’ endless conversations would circle around some point of fact: was Labrador ever a province unto itself? What are the cultural origins of Kokopelli? After persuasive arguments had been made on both sides and convinced no one, there was only one recourse left: the gigantic Random House dictionary that stood on its own special shrine in my grandparents’ dining room. Those thin pages with half-moons cut out on the edge to help you navigate from letter to letter, that special atlas inset in the back, didn’t always resolve the question; sometimes they just provided a foundation for a new argument. But there was a pleasant kind of faith in the activity, which took The Dictionary not as an invincible authority in itself—we knew it was incomplete and fallible—but as a stand-in for the possibility of reaching consensus on the terms of our shared world. (At least, that’s how it seems to me in retrospect.)

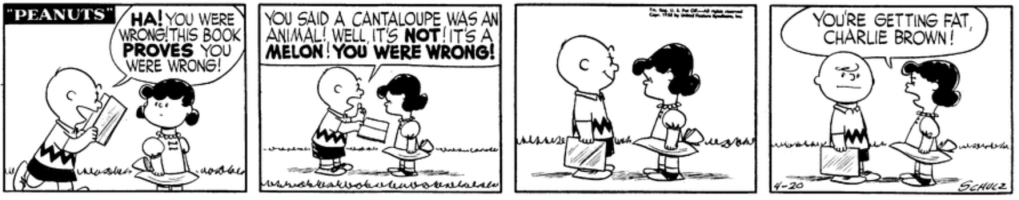

Peanuts characters don’t consult a literal dictionary on an altar, but I recognize the spirit of “going to the dictionary” in many of their interactions. “This book proves …” “This book says …” “It says here …”

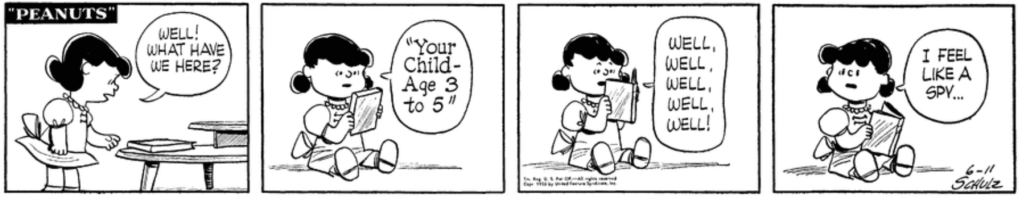

Short take #1 is just that the Peanuts kids use books the way I grew up using them, and this surely has something to do with my attachment to the strip. Sometimes, as the work of Leah Price would suggest, we affiliate with other people based on not what we read but how we read. For instance: if your parents kept child-rearing manuals around the house, did you ever peek inside to try to understand what your habits and foibles “meant” from an adult standpoint? Because Lucy and I did:

I told you this take was short! But I’d be remiss if I didn’t contextualize two of the “going to the dictionary” examples above, since they’re kind of perplexing when isolated from their original theme-and-variations. (The first example, the cantaloupe one, stands alone—rightly so.)

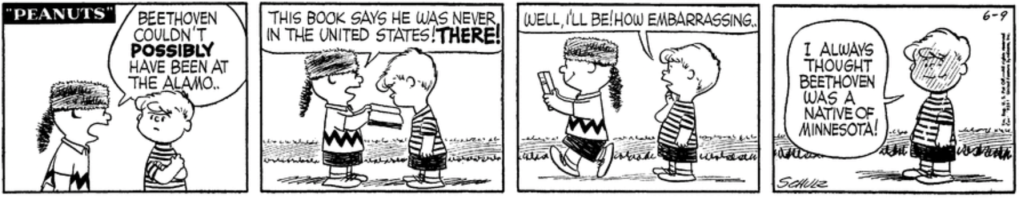

The Beethoven-at-the-Alamo triumph comes from a (to me) bizarre theme-and-variations that recurs intermittently over the course of 1955, in which Charlie Brown and Schroeder argue over who was more heroic: Davy Crockett or Beethoven. A bit of background research and asking around reveals that the nation was swept by a Davy Crockett craze that year, in the wake of a Disney miniseries about the famed bear-whupper. Who knows how differently the baby boomers might have turned out if Disney had produced a Beethoven hagiography instead? At any rate, Charlie Brown eventually reaches saturation point on Crockett merch and ends up burying his coonskin cap, which feels like an allegory for something, but I’m not sure what.

As for the third example, Charlie Brown has to prove to Lucy that the earth isn’t really shrinking because she’s spent the whole week insisting that the cumulative erosion of human feet is “wearing down the earth.”

Note how well this bleak vision fits with Lucy’s attempt, only a year previously, to draw a line “clear around the earth”; she’s still obsessed with quantifying the universe. This particular theme-and-variations made a big impression on me when I first encountered it as a child, because while I understood that Lucy’s idée fixe was ridiculous, I couldn’t quite explain to myself why it was. Come to think of it—if you asked me now—well. This may be a job for Randall Munroe.

III. Imitation games

Nobody who reads Blockheads will be surprised to learn that I once managed to write a grad school paper about Peanuts. The prose was awkward (but with occasional gems, e.g. a footnote declaring that “Snoopy’s virtue is not monotheistic but pagan”), and it had an irritatingly long title (“‘If You Really Are a Fake, Don’t Tell Me’: Situational Character and Charles Schulz’s Ethic of Innocence”). Skimming through it now, though, for reasons that will become clear in a moment, I think I stand by the argument, and one claim in particular. In non-academic terms, the thesis is this: Snoopy’s transformation into Snoopy—into the playful, imaginative, highly emotional beagle we know and love—began when he started to imitate animals and even specific characters in the strip. The complex repertoire of characters that Snoopy eventually embodies, from the WWI Flying Ace to Joe Cool to the struggling writer to the tennis pro, should be read as an extension of these initial acts of imitation: Snoopy achieves complexity by mimicking, riffing on, and remixing the behaviors of the creatures around him. (If there’s an affinity between Snoopy and jazz—despite the fact that Schulz apparently, and depressingly, didn’t like jazz!—this might be part of the reason.)

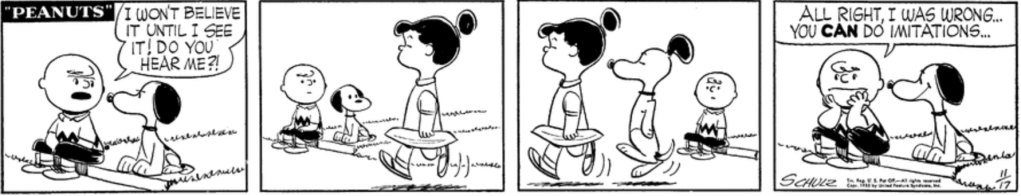

These imitations begin in 1955. In February, Snoopy gets his first theme-and-variations all to himself when he pretends to be a rhinoceros; by September, he’s trying out the role of snake, with equally disappointing results. These little episodes set up a template that will occasionally recur: Snoopy, simmering with righteous anger, fantasizes about being an animal more powerful and intimidating than a dog (“Then I wouldn’t have to take anything from anybody!”), only to find that he can’t seem to scare anybody. It’s a funny formula, giving Schulz a chance to make some great drawings and lend a bit of depth to Snoopy’s character: you’ll note that his internal monologue seems to be getting more consistent in these strips. But as 1955 draws to a close, Snoopy remains relatively detached from the social world of the kids, who mostly notice him when he’s begging for candy. And then, in November, this happens:

This isn’t just the first time Snoopy imitates one of the Peanuts kids, although that certainly is significant—especially since the feature he caricatures is Violet’s ponytail, which, as I’ve argued, can almost stand in for the idea of instant comic-strip recognizability. It’s also a very early instance—quite possibly the first—of Charlie Brown responding to something that Snoopy couldn’t possibly have told him. What non-verbal action could Snoopy possibly have taken—short of actually imitating someone, which apparently he hadn’t yet done—to make Charlie Brown respond with incredulity in the first panel? None, I think; so we’re left to assume that Snoopy has somehow communicated a verbal proposition to Charlie Brown. Within the rules of the strip, this is both impossible (Snoopy canonically can’t speak) and something that happens fairly often. Why does it matter? Because it brings Snoopy into the children’s social circle, into their sphere of interaction; even before he’s on his hind legs à la Violet, it makes him less of a dog and more of a person. And if, as we saw with Charlie Brown and Lucy, characters become who they are by interacting with other (also half-formed, also evolving) characters, then this strip marks a watershed for Snoopy. From here on, he’s not just a dog who sometimes imposes on the kids; he’s an individual to whom they have to respond—which means they’ll exert a shaping pressure on his character, and he’ll exert a shaping pressure on theirs.

So: welcome to the gang, Snoopy! Like Charlie Brown (but less grudgingly), Peanuts readers will soon come to admire your ability to remake the world in your image—and vice versa.

IV. Five hundred years from now

A few years ago, J.D. Porter drew my attention to an interesting moment in the Bible. In 1 Kings 16, we learn about Zimri, a military commander who slaughters King Elah and all his family members so that he (Zimri) can seize power. His reign is short: the military throws their weight behind a different claimant to the throne, and Zimri ends up burning the palace down with himself inside it after only seven days as king. One Biblical commentator declares that Zimri “had little impact other than the removal of the house of Baasha”—which is surely true, as far as history and politics go. But Zimri’s cultural impact, J.D. told me, outlived him by several generations: in 2 Kings 9:31, when Jehu is murdering everyone left in the House of Ahab to complete his ascent to the throne, Jezebel sardonically greets him as “Zimri”. (Then he tells her servants to push her out the window, and they do, and he tramples her under his horse’s hooves, and her body is ultimately eaten by dogs; so much for Jezebel.)

Different English translations render this moment differently: in the King James Version, Jezebel merely reminds him of Zimri’s fate—”Had Zimri peace, who slew his master?”—while other versions have her actually call him by the traitor’s name—”Is it well, Zimri, your master’s murderer?” or “Is it peace, you Zimri, murderer of your master?” The only version that doesn’t capture the line particularly well, in my uninformed layperson’s opinion, is the New Living Translation, which renders Jezebel’s words thus: “Have you come in peace, you murderer? You’re just like Zimri, who murdered his master!” Now, of course, this is exactly what Jezebel means when she addresses Jehu as Zimri; he has conspired to kill King Jehoram and all his family, just as Zimri annihilated the house of Baasha. But to spell it out in this way misses what I find so fascinating about this moment: the interpellation of the reader. When Jezebel casually calls Jehu a “Zimri” and leaves it at that, she assumes that Jehu will know what she’s talking about—just as I could address someone as “you Quisling!” rather than explaining, “You’re collaborating with an authoritarian dictator against the public, just like Quisling did!” And, in turn, the writers of 2 Kings assume that the readers of Kings will share that cultural reference point.

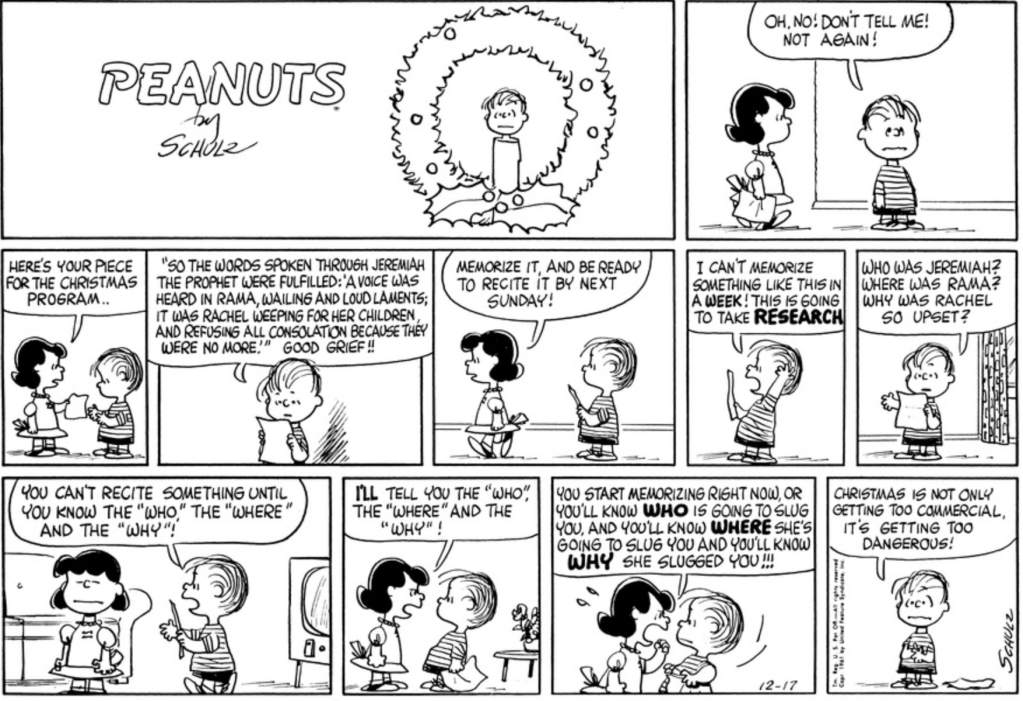

Of course, we might not share it—we almost surely wouldn’t if 1 Kings didn’t exist already—but reading a passage that demands that we do more reading, that we embark on a reconstructive enterprise to make sense of even a single sentence, is, to my exegetical mind, part of the fun. “Who was Jeremiah? Where was Rama? Why was Rachel so upset?”

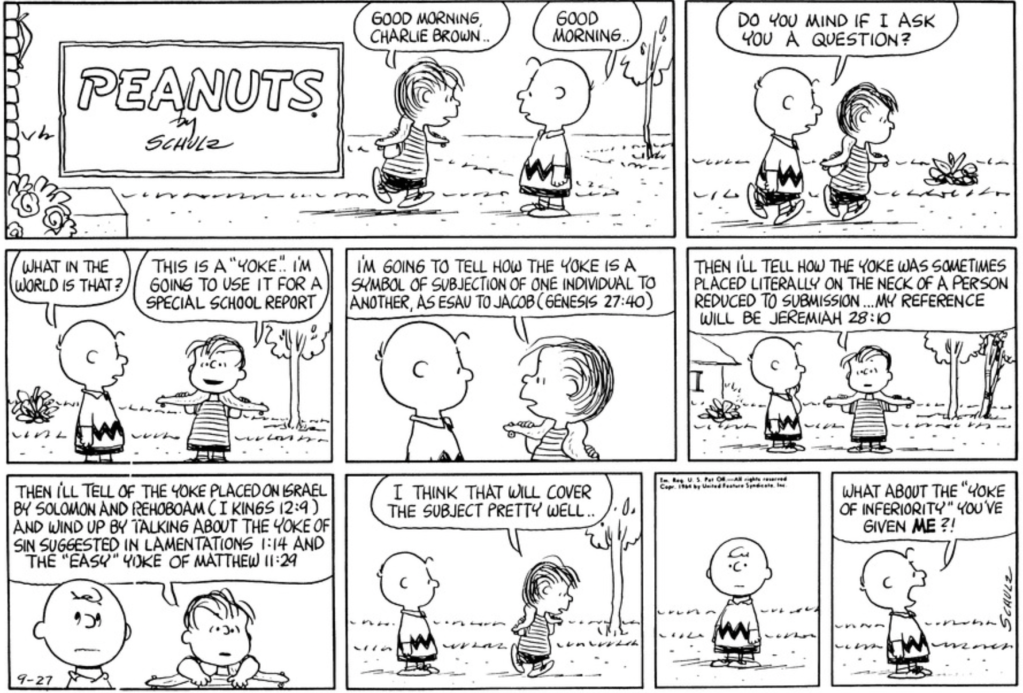

Now, Linus is, of course, the Peanuts character most likely to do this kind of research. Remember his (Sunday?) school report on the “yoke” as Biblical metaphor?

But both of the Sunday strips above are from the early ’60s, and in 1955 Linus has only just learned to talk; early evidence of precocity notwithstanding, it will take a little time before he becomes the familiar gentle scholar. Even so, this set of associations might help explain why, when I discovered a Zimri moment in this year of Peanuts strips—that is, a moment when characters in a narrative invoke as a cultural reference point something that happened earlier in the same narrative—it felt right to me that Linus was at the center of it.

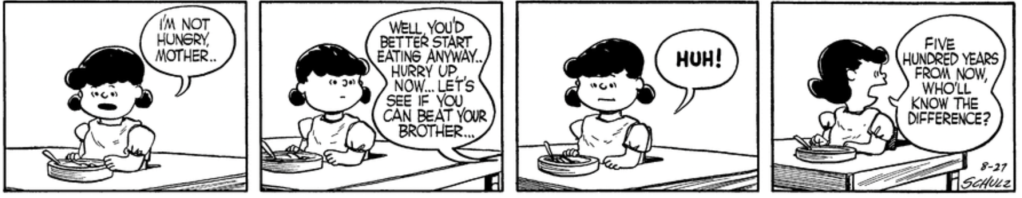

To explain this moment, I’ll need to take a brief trip back to 1954, when Lucy dismissed her mother’s attempt to incentivize her good behavior with characteristically macrocosmic perspective:

This made me laugh, and I didn’t think much more about it. When I encountered the same phrase almost a year later, but now in Linus’s thought balloon rather than Lucy’s speech, I initially assumed Schulz was reusing the joke—a bit surprising, since I hadn’t expected to see that so early in the strip’s life, but not unheard of:

A couple of months go by, and Linus learns to talk, and Mrs. Van Pelt keeps trying new strategies to get her children to behave; and then, in September 1955, we find this:

Linus goes on to use this rejoinder several more times—so often, in fact, that it gets remembered as one of his catchphrases, at least in Matt Groening’s (very good) introduction to the 1955-56 volume of the Complete Peanuts. But it’s easy to miss, if you’re not reading obsessively and chronologically, that Schulz isn’t simply adding a funny lead-up to the punchline when he makes Linus reference an “old saying.” For Linus, “Five hundred years from now, who’ll know the difference?” feels like an ageless aphorism because his sister said it—recently enough that he was alive to hear it (“Let’s see if you can beat your brother”), but long enough ago that it would seem like eternity to a toddler. For the adult Schulz, of course, the gap between Lucy’s first use of the phrase and Linus’s adoption of it was scarcely more than a year, and there’s no doubt in my mind that he left us this Easter egg intentionally. When the scale of a story becomes immense, it begins to self-organize; not content to serve as a touchstone for readers in our world, the story-world begins to acquire an internal culture, an internal canon of people, phrases, and events. If Schulz is more self-conscious about this than most—well, after we saw him meditate on scale so pertinently and persistently in 1954, we shouldn’t be surprised.

When I first noticed this pattern, I Googled “Five hundred years from now, who’ll know the difference?” to make sure it wasn’t a reference to some non-Peanuts cultural artifact—and found it over and over again on websites like quotefancy.com and wisefamousquotes.com, always attributed to “Charles Schulz.” By now, in other words, the phrase really is an “old saying”—one that, perhaps not by accident, takes posterity as its explicit subject. The question may not be as rhetorical as it seems. Five hundred years from now, who’ll know the difference between Linus and Lucy, between Peanuts and Pogo? Well, if I have any say in the matter ..

V. Rituals

First of the Week

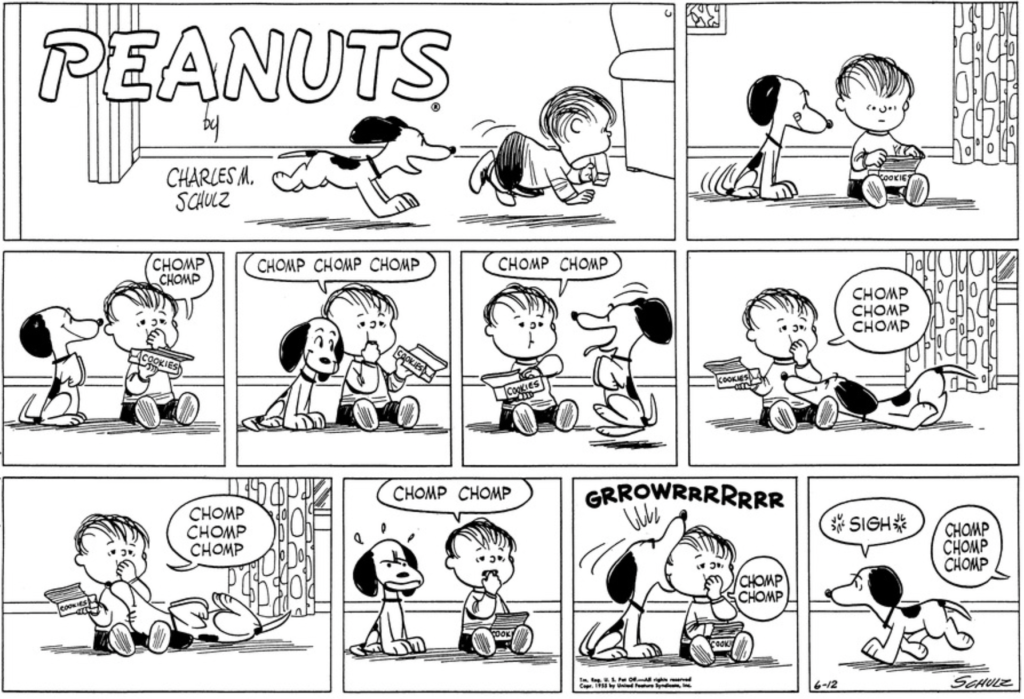

The kids in Peanuts sigh. They sigh so often, and in such a conventionalized form (“*SIGH*”), that when I was a kid I assumed “sigh” was a word that people said in moments of disappointment rather than a label for a nonverbal sound. I can’t be absolutely positive that “sigh” makes its debut in Peanuts this year; I first noticed a couple of “sigh”s (set apart by their serif font) in May 1955, but I may have missed an earlier example. I can, however, point to what I think is the first appearance of a proper asterisked Peanuts sigh, in this wordless but sound-packed strip:

Panel of the Week

Your friend,

Hannah