Blockheads #5: 1954

First published May 29, 2020

A note on May 29, 2020

Charles Schulz was from St. Paul. He seems to have been an ethical but not especially radical white man of his era, so I can’t say whether he would have stood in solidarity with the protesters in Minneapolis. But I do, and you should, because the Twin Cities deserve to be free. That’s the right way to love your city, or any city, for that matter: support those who are fighting to make it free and just.

If you’d like to join me in doing so, please donate what you can to the Minnesota Freedom Fund or Reclaim the Block or Black Visions Collective or North Star Health Collective. Or all of them at once! And find similar organizations in the city that you love, wherever that might be, so that you can support them too, when the time comes.

In love and solidarity—here’s Blockheads.

I. (time)

I don’t think I’ve mentioned (although my Instagram followers might have seen) that I keep a little gray Moleskine for my Peanuts notes. When a strip is particularly funny, strange, or surprising, I make a note of it in my tiny handwriting, including the date for reference; I index the pages by date range in the top margin. For the first couple weeks of this project, I was jotting things down at a rate of about 4-6 months per page, and every so often a month would go by with only two or three strips I found noteworthy.

Now that I’m up to 1954, though, I’m lucky to squeeze more than 2 months on a page. In part, I’m sure, my standards of salience are changing: as new motifs keep getting added to the Peanuts symphony, more of the jokes seem to fall into some existing pattern or shed light on a familiar character. The strip is getting funnier and smarter, too, gathering steam every year in just the way you would expect from a system crossing new thresholds of complexity. But I also suspect that Schulz’s interests had periods of varying duration, and that within the longer time scales—we’ve been in the Lucillene Era since mid-1952, I’d argue—there may more or fewer short intervals, some of which represent variations on the overarching theme (the Fussbudget Period, the Age of Measurement, etc.) and some of which are almost unrelated (the Pig-Pen Epoch). Dating any given Peanuts strip is mercifully easy—just check the corners of the last panel)—but it’s as complicated to locate oneself in this panorama of Schulzian time as it is to find one’s place in Proust’s “interpolated calendar of happiness”, and for similar reasons.

II. (theory)

1954 seems, to me, particularly dense with overlapping time frames, including a new kind of narrative time—one that seems to come into existence only in this year, and that will come to be incredibly important to the narrative logic of Peanuts. I don’t know quite what to call it, because, in a grave critical oversight, I don’t believe it’s ever been named (although I’d love to be corrected on this!). Comic strip scholars draw a clear distinction between the story strip, which develops a long-form narrative in daily installments—think Brenda Starr or Mary Worth—and the “gag-a-day” strip. Whereas the former type usually isn’t going for humor, the latter type, as the name implies, focuses on yuks that can be generated within the confines of four panels, starting afresh every day and avoiding serial plot lines. Peanuts is a gag-a-day strip. There’s total consensus on this among comics people, and for very good reason: the majority of strips in any given year are one-offs—drawing, of course, on the established habits and dispositions of the familiar characters, but not building toward any kind of lasting change, and always structured around a joke.

But Schulz was also a master of something that falls between the gag-a-day and the story format, and this is what I’m having trouble defining. The multi-strip narrative? The extended episode? The Week—on the grounds that the six weekday strips seem to be the most natural length for this narrative unit, although individual examples of it might last longer or shorter than a week? In earlier experiments with writing about this, I’ve been tempted to call it a serial embedded within the series that is Peanuts—but that’s not quite right, because the individual strips in this sequence could usually be shuffled without any loss of narrative continuity. Let’s work from an example, one of maybe a dozen to appear in ’54:

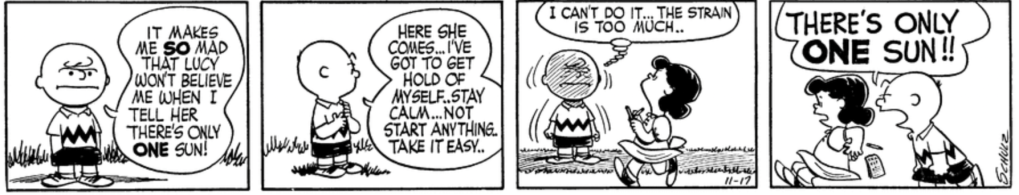

Not only do these strips—which appeared in sequence from Monday, November 15 to Friday, November 19—not build to any particular conclusion (unless it be the continued unraveling of Charlie Brown’s psyche); Schulz actually seems to take pains to restate the premise of the joke each time around, although he’s fairly clever about doing so. (A line like “You think you’re counting a new sun every day, don’t you?” wouldn’t necessarily pass for realistic dialogue in, say, a Grace Paley story, but it’s a pretty economical way to accomplish the daily reset that’s expected in a “gag-a-day” strip.)

Eventually, Schulz will pursue some story lines that require serial development: Snoopy’s doghouse will be threatened by bulldozers, destroyed by a fire, rebuilt; Linus and Lucy will move away and then return; and the strip’s longest run of continuous story will begin with Charlie Brown hallucinating a baseball in place of the sun and end with him being elected camp president while wearing a sack on his head. (The kids call him “Mr. Sack”. Much more on this in four or five months!) The individual strips in these narratives still have punchlines, with only the rarest exceptions, but the stories they tell do constitute discrete events: theoretically, if characters in Schulz ever reminisced, they could reminisce about these. By contrast, the kind of sequence I’ve identified above constitutes not so much a memorable episode in the characters’ lives but a kind of background that, once accumulated enough, resets their expectations for each other—and ours for them. Eventually, Charlie Brown will learn to recognize (and dread) the moments when Lucy seems to be gearing up for a flight of pseudo-scientific gibberish at about the same time we recognize them. The characters’ ability to track these patterns, to see themselves and each other as participants in recurring motifs, allows for a peculiarly pleasing (in my view) kind of not-quite-meta wink: the characters notice the narrative constraints on their lives, not because they have some kind of preternatural awareness of their fictionality, but because the lives of non-fictional humans are also constrained by habits and loops, themes and variations.

This last term, suggested to me by J.D. Porter—theme and variations—is, I think, the best label for the kinds of (usually) week-long narrative structures I’m talking about here. The five strips above don’t form anything like a linear serial narrative, but they’re also held together by something a bit more precise than a shared topic (like, say, swimming pools or homework). Instead, Schulz has come up with a narrative premise that bears exploring from multiple angles and licenses multiple jokes, so he sustains that premise over several days. It’s unclear in what temporal relation these little scenes are supposed to stand with each other: Charlie Brown and Lucy might be having this conversation on sequential days, on the same day, or at irregular moments over the course of months for all we know. Diegetic time is less important here than the reader’s time, which the theme-and-variations helps to structure precisely by refusing to move on—by representing the accreting time of habit rather than the unfurling time of conscious experience.

Eventually, Schulz will manage to create multi-week serial narratives (say, Lucy buries Linus’s blanket –> Linus suffers –> the blanket is restored) that contain theme-and-variations (Linus suffers in a multitude of ways over several strips that follow roughly the same internal arc) that contain a gag a day (this one, for instance). It’s in these complex narrative structures that the Proustian “interpolated calendar” really comes through (although “happiness” isn’t what poor Linus is feeling). Let’s take a given hour in my life—say, one in which I’m waiting for some news that could be either very good or very bad. That hour is part of a linear event-narrative: I pose a high-stakes question –> I wait for the response –> I receive the response and my life changes in one direction or another. It’s also part of a recurring pattern, because whatever the particular news I’m waiting for, I tend to behave in a similar way every time I’m kept in suspense: I bite my nails, I try in vain to distract myself, I cycle through excited anticipation and depressive dread. But the echoes aren’t only affective: if I’m fruitlessly distracting myself with, say, a crossword puzzle, my consciousness and behavior in this moment also forms part of a broad crossword puzzle pattern in my life, so that I might in the future remember that the glacier-fed Alpine river is “AARE” because I saw it in this puzzle, without remembering the anxiety that tinted the puzzle at the time. People sometimes seem to think that Proust’s stature as a theorist of time has to do with a special ability to represent the experiential flow of time, but I don’t think that’s really his primary interest; and Schulz, working in the comic strip form, positively couldn’t represent that flow. One of the reasons I often find myself comparing the two, though, is the ability they both have to color in the tiny squares of that interpolated calendar so that it makes a mosaic.

III. (counting)

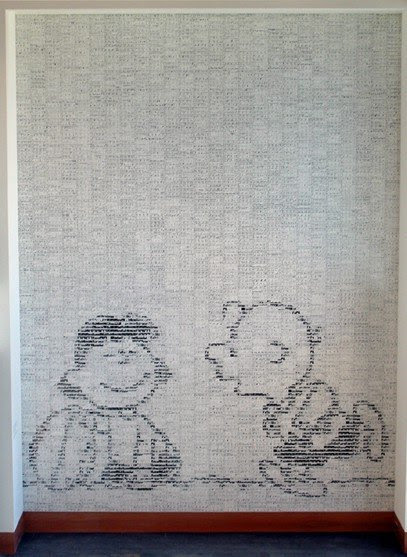

Lucy thinks she’s counting the suns. I initially settled on this sequence as an example of theme-and-variations because it matched the formal features that I wanted to identify and label. But the content of the sequence also turns out to be strangely characteristic, because the Lucy of 1954 counts everything. She counts raindrops:

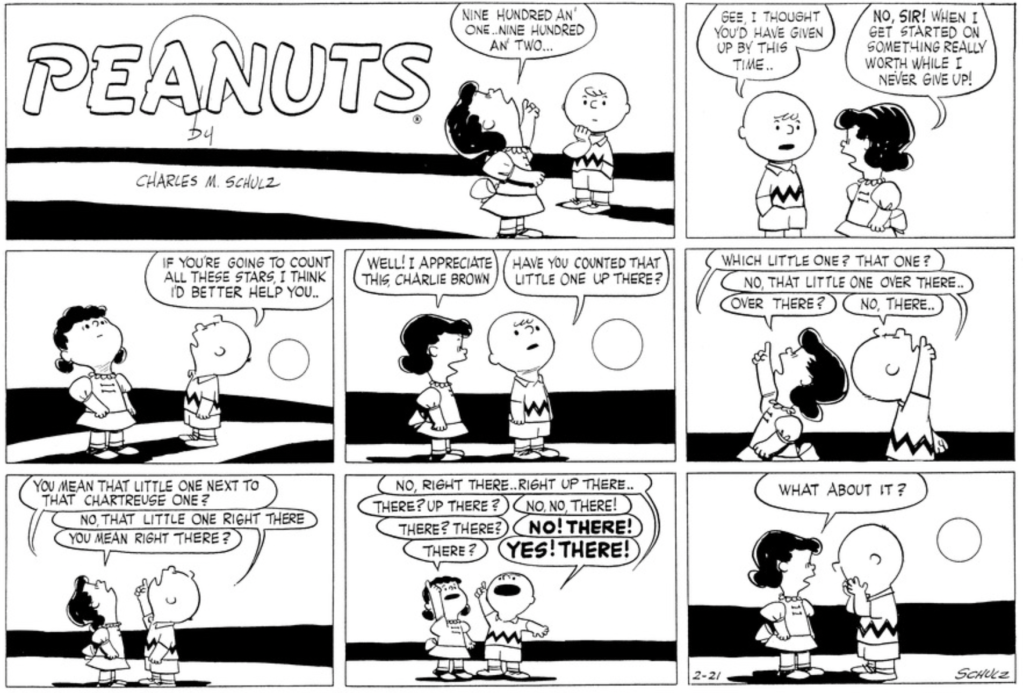

She counts stars:

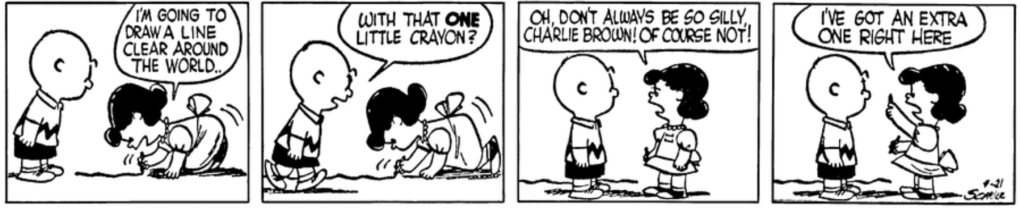

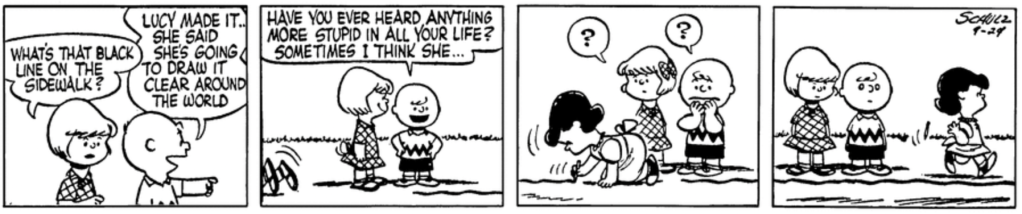

And although she can’t exactly count earths, she tries in her own way to quantify and contain the globe by drawing a line “clear around” it:

You’ll recognize this last sequence as a theme-and-variations, and one that gets tied off rather more definitively than most. (Charlie Brown’s look of utter dismay—not confusion, but something like horror—when Lucy connects the two lines strikes me as a brilliant touch.)

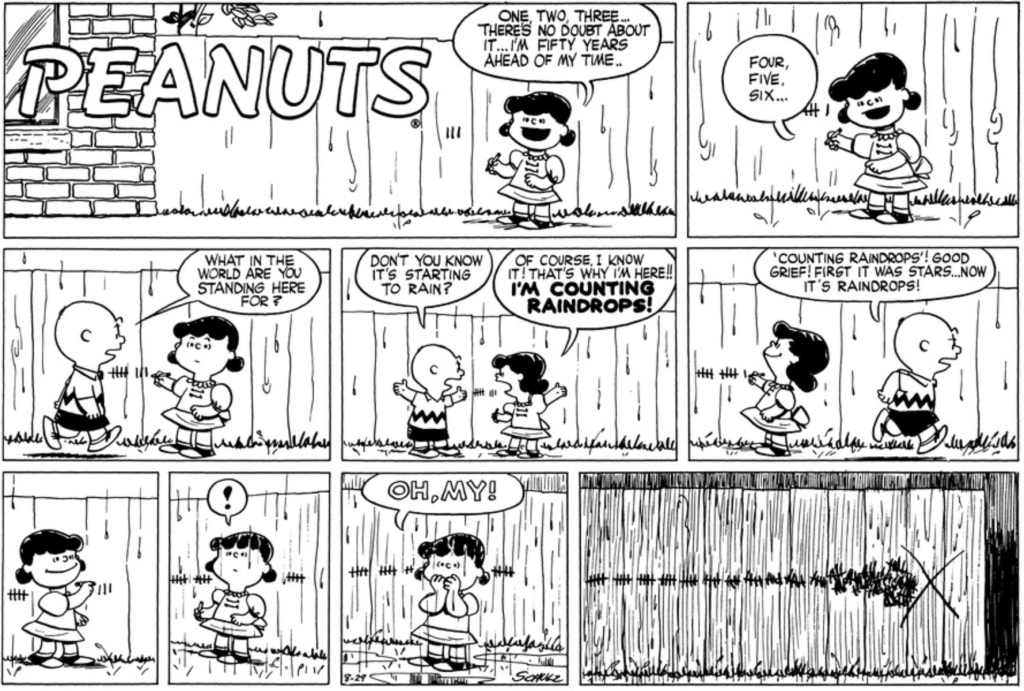

Now, not all of Lucy’s attempts to measure the cosmos appear as theme-and-variations: the raindrop counting is a one-off (although Charlie Brown’s reaction reminds us of previous counting sessions), and the star counting recurs only in Sunday strips, which is, I think, a qualitatively different kind of repetition. But I suspect there’s a non-accidental connection between Lucy’s counting obsession—which she never applies to, say, bugs or grains of sand or leaves, but only to entities of the grandest scale—and Schulz’s discovery/invention of the theme-and-variations form. Is it the same sun, or multiple suns? Is it one narrative or multiple narratives—or perhaps the same narrative cloned as many times as it takes? Can the round world be flattened and enfolded within the confines of a comic strip?

To put it bluntly: Lucy is trying to put sublimity into a numbered series of little boxes, just like Schulz. And it’s worth noting that the confidence she brings to the task doesn’t prevent her from getting overwhelmed sometimes:

![A Sunday strip. In the title panel, Lucy sits at what looks to be an adding machine, smiling as a procession of brilliant stars rolls by in front of her. "I'm going to count all the stars even if it kills me!" she says, walking outside with a sheet of paper. "People say I'm crazy, but I know I'm not, and that's what it counts!" Over the next few panels, Lucy sits on the curb happily, "mark[ing] 'em down as they come out." Soon, however, they're appearing too fast: "Eleventwelvethirteen! Oh, my! They're coming out all over! SLOW DOWN" Lucy runs around panting, counting desperately. In the final panel, she sits on the curb exhausted in front of a dazzling starry sky. "Rats!"](https://blockheads.blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/screen-shot-2025-01-20-at-10.32.38-am.png?w=1024)

The star-counting scenes contain some of Schulz’s most pleasing art, I think—from the stark bright abstraction of the February 21 strip above to the delightful title panel of this strip from April 4, where Lucy cheerfully works an adding machine (?) as twinkling stars file before her. This particular strip also includes one of my favorite deadpan throwaway lines: “People say I’m crazy, but I know I’m not, and that’s what counts!” Lucy’s determination is far from what we would usually consider art (even farther, perhaps, than it is from what we would consider science)—but it might capture the combined optimism and exhaustion of a man who took exactly one vacation in fifty years of work. In the end, a universe glitters around her, revealing itself too quickly to keep up. “Rats!”

IV. (bonus content)

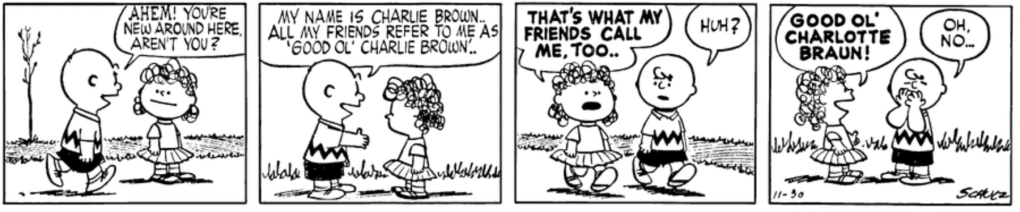

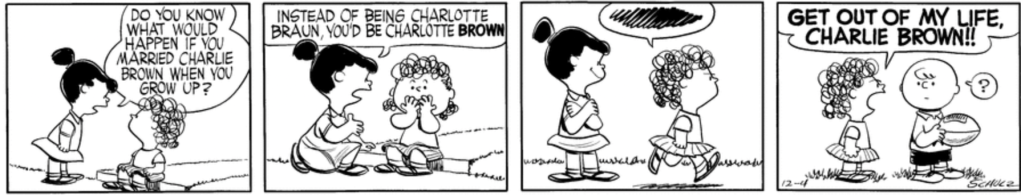

That ends this week’s argument, such as it is. Since I missed last week due to non-Blockheads writing obligations, though, I think I ought to leave you with an extra little treat: my favorite strip in this Peanuts volume (1953-54), and one that reliably makes me crack up. In addition to specific scenarios involving Charlie Brown and the gang, theme-and-variations are sometimes structured around peripheral, relatively flat characters. Take Charlotte Braun, a curly-haired, wide-mouthed girl who has trouble controlling the volume of her voice:

Charlotte’s comedic potential reaches its peak, in my opinion, in this strip, which incidentally also demonstrates Violet’s love of stirring the pot:

V. (rituals)

First of the Week

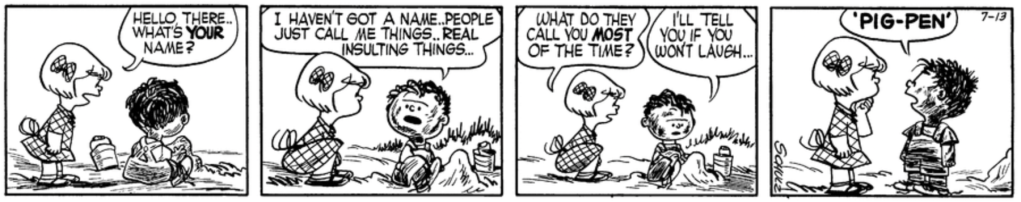

July 13, 1954 marks the first appearance of everyone’s favorite walking dust cloud:

Patty, in characteristic fashion, both introduces Pig-Pen around the neighborhood and continues to make catty little remarks about him. But I was surprised and charmed to see how Lucy greets him, in a tone that somehow reminds me of Fred Flintstone’s introduction to Weirdly Gruesome:

Panel of the Week

Your friend,

Hannah